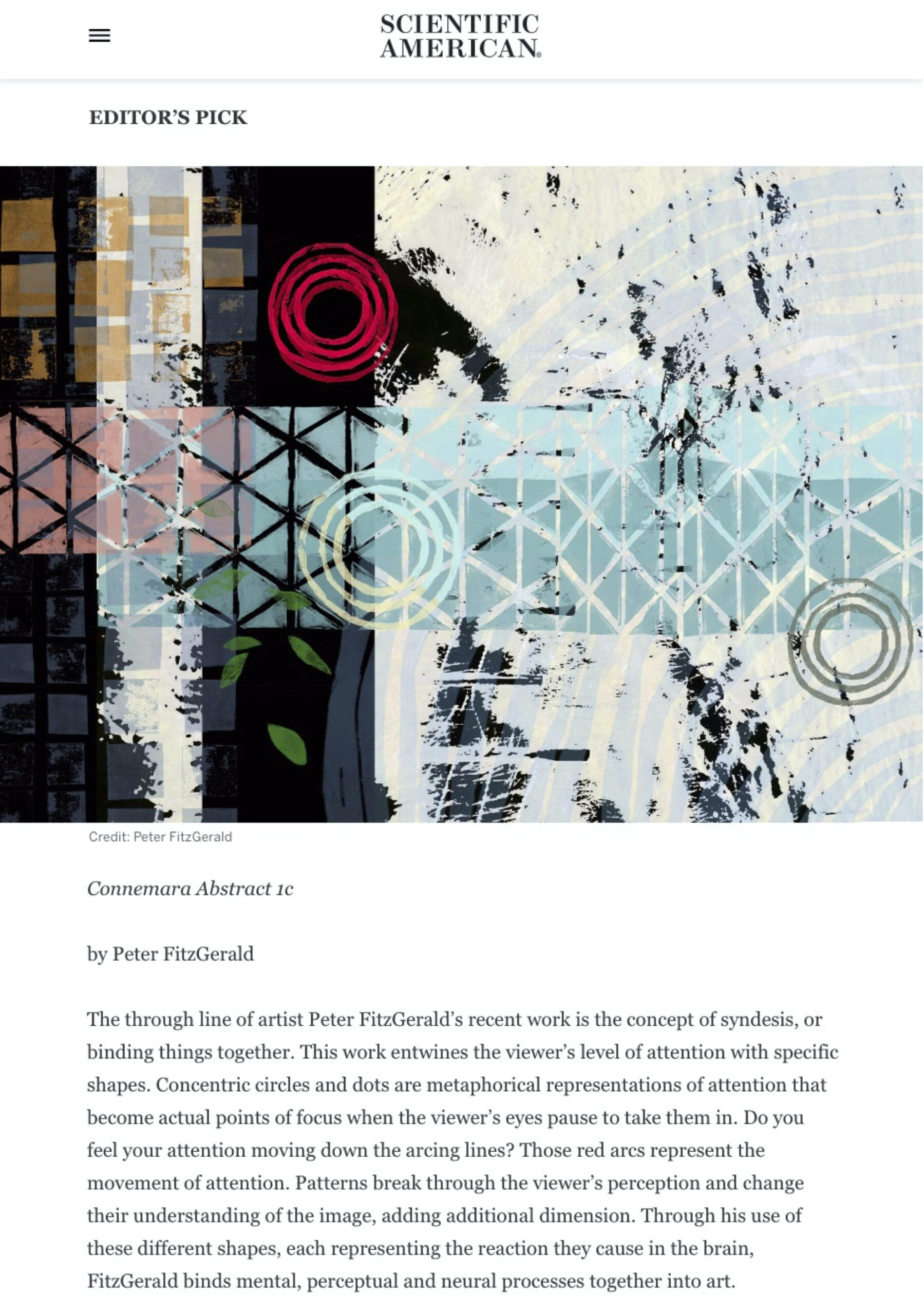

Peter FitzGerald: ‘Connemara Abstract 1c’; digital print based on lino cuts and photograph

Very pleased to have been included among the ‘Editor’s Picks’ on the Scientific American website, August 2022; more here.

Syndetic art

What happens when we look at a work of art? A great deal, obviously, but the processes, particularly the higher-level ones which make looking at art worthwhile and meaningful, are poorly understood. I want to use art itself to research at the interfaces of visual art, cognitive psychology, and neuroscience (and possibly also AI). This is an approach from the ‘wrong’ end, compared to the scientific method, but I believe that I can make new art that ‘binds’ components of the artwork to higher-level processes in the viewer.

From Galway. I have a D Phil in Experimental Psychology from the University of Oxford, specialising in memory and attention, and I have done research and published at both pre- and post-doc level. In a change of course, literally, I graduated from NCAD in 1995 with a first in Fine Art painting. I have exhibited widely but sporadically. From 1998 to 2011 I was editor of Circa Art Magazine. More recently I have worked on many web and print projects as editor, coder and / or designer, while continuing to make art.

Ultimately, the domains of art and science are about the same thing: what it means to be us. But when science attempts to decode the arts, the arts tend to respond with, in Eliot’s words, “That is not it, at all.” Science breaks a thing apart. The arts point out that the thing is now broken. The two tendencies aren’t entirely at odds; for example, Modernism’s trend towards minimalism sought to discard the inessential … until it too felt broken.[1]

MoreI want to approach the problem from a different angle: to ask whether we can create successful artworks out of visual tropes, devices, etc. – ‘components’, in short – such that art and science share a visual lingua franca. This new language would be as amenable to analysis as it is to creativity. In particular, there are components I call ‘syndetic’, meaning that there is an apparent, predictable binding between them and perceptual and cognitive processes. Imagine a situation, for example, where the viewer knows that painted concentric circles represent focused attention. When the viewer deploys that knowledge while looking at these circles, there must be a binding from the physical imagery right up to a higher cognitive state. See the ‘Scientific American’ print to the right / below for some of these ‘attention circles’ in situ, mixed with other components. There is precedent for a component approach in painting. For example, there are lengthy series of sculptural and painted works by Picasso, from around 1914, in which some components appear repeatedly.

I’m not aware of a component-based, syndetic-like initiative being used elsewhere, in the way that I am suggesting.[2] There is an instructive similarity, though, in the near- opposite approach of James Turrell (a psychologist initially), where there is a sort of double cognitive dissolution. [3]

The overarching aim of this component-based approach is to create artworks that are credible both as scientifically useful imagery and as art. Hartley and Poeppel (2020, p. 597) suggest that “In the best of all possible worlds, one should learn both something about the [arts] domain in question … and something principled about neurobiology” (neurobiology being their specialisation; their italics). We can hope that the knowledge gained by a new approach is bi-directional.

Pattern is of specific interest to me; it is something that I am very keen to study and experiment with. There are at least three reasons that it is so interesting:

More2D-3D rivalry

Pattern is bound / syndetic from the start: it is surface and it calls attention to surface. But this may be a 2D surface, a 3D depicted one (or a bit of both), or an actual 3D surface.

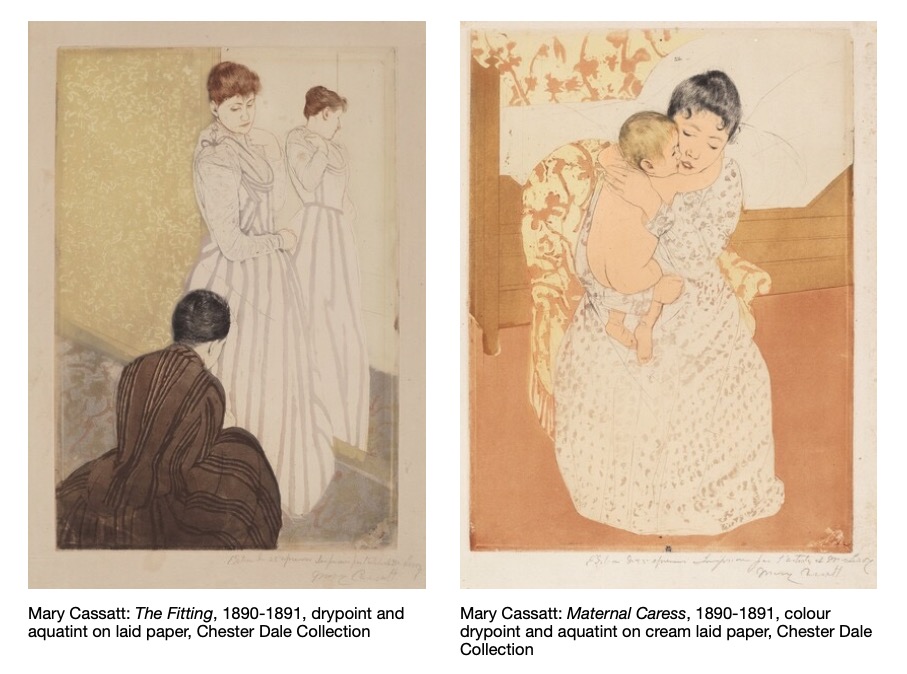

See for example these prints by Mary Cassatt:

What is happening when we encounter such surfaces, what is pattern doing as we look at it, especially in this unstable 2D / 3D ‘Cassatt’ form? I hope to open up such questions, both through components in my practice, and at a cognitive-science level…

The forgotten art movement

…but to open it up too at an art-theory level by – in this case – examining in detail the Pattern and Decoration movement (‘P&D’; 1972 – 1985, approx.) as part of my research. Danto (2007, p. 10) says of P&D, “It is a genuine insight to recognize … that there is ‘a third category of art which is neither representational nor abstract’ – the art of ornament, pattern, and decoration.” He is nonplussed by P&D’s omission from the Art History canon (ibid, p. 11). [4]

The missing subject

Joyce Kozloff: Hidden Chambers, 1975-76; the work is approx. 2 x 3m; image held here There’s an extra puzzle with many P&D and later works where pattern is the image: they lack a conventional subject matter. The Joyce Kozloff work above is typical. This absence appears to be another way in which pattern is fertile ground for investigation.

Future pattern

I strongly suspect that there is a vast amount left in P&D, this “third category of art” which got dropped. I am drawn to pattern and how it functions, and I am fascinated by works where rich pattern and flattening create perceptual confusion between 2D and 3D interpretations. The question, for me, is also to what extent syndetic components could add an extra dimension to such works.

Finally, this work below demonstrates how rich pattern can be.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby: “The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born” Might Not Hold True For Much Longer, 2013; image held here It’s is a great time to be in this research area. Synergies across cognitive psychology, neuroscience, philosophy and AI mean that, steadily, more credible models have emerged for how we understand the world. We can now theorise, with empirical back-up, about how our bodies and brains construct our cognitive processes (selves, minds), and how these processes give form to our non-conscious and conscious being in the world. [5]

MoreThe conceptual space to which I hope to contribute is not new; it’s been a source of fascination and frustration going back centuries. It’s at the intersection of four groups: artists, scientists, thinkers, and anyone who encounters art. A growth of knowledge in this space would offer many things. The artist may shape works in a new way, knowing how to effect different outcomes (a similar point is made by Carew and Ramaswami, 2020). The scientist may test, analyse and explain in a more real but also more targeted way. The theorist may revise. The viewer may be able to think, “I understand how a lot of this is working.”

I believe (1) that we may be able to create a lingua franca of pictorial components that bind to perceptual and higher processes; and (2) that they may work equally as art and as a tractable approach for the cognitive sciences. It’s even possible to imagine (admittedly as a non-practitioner) analogues of ‘attention circles’ and the like in other artforms – music, poetry, etc. In the arts and sciences we’d no longer be talking past each other.

MoreThere’s an allied possibility: if the cognitive sciences can get a better handle on the arts, these insights may change the way we make art. And with AI ever-encroaching, we need to understand what’s human in what we create.

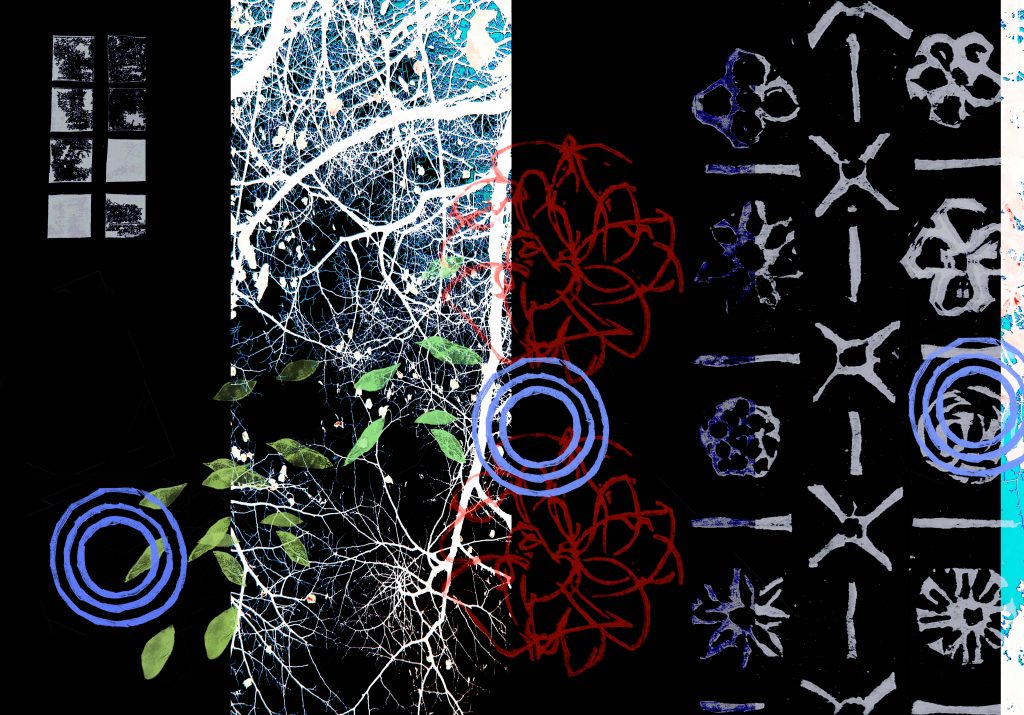

Scientific American asked to place one of these three recent ‘syndetic’ pieces of mine onto their website.

More Connemara Abstract 1c; digital print

Connemara Abstract 1c; digital print Horizontal Abstract 14b; digital print

Horizontal Abstract 14b; digital print Horizontal Abstract 17b; digital print

Horizontal Abstract 17b; digital printThey eventually chose the top image, and placed it on their See the Top Entries in the Art of Neuroscience Competition page.

The works here are all based on cut lino used to print oil colour onto paper or canvas. I scanned the results then photoshopped them to play with compositions for painting. But when I saw that I was going to be in time for the Art of Neuroscience Competition I expanded the experimental stage and created this website.

Note: These works need to be viewed under the general instruction that these are not usual artworks, that they contain components that are designed to engender a perceptual and / or cognitive effect in the viewer. In some cases, there would also be a more specific instruction – as in “Imagine that the concentric circles represent your focus of attention. What do you feel when you focus on the circles and think about that?” (or similar sort of instruction)

The write-up in Scientific American…

…does a pretty decent description of the syndesis concept. The image described doesn’t correspond entirely to the image chosen, and it is perhaps more related to other images on this site, e.g. the one below.

Vertical Abstract 16b; digital print

Vertical Abstract 16b; digital print- Chatterjee (2014) gives a very good introduction to thinking and research at the arts-science crossover, though I find one or two of his explanatory mechanisms unlikely. There’s a useful overview of some recent arts-related neuroscience thinking in Carew and Ramaswami (2020).

More- The syndetic approach is about prompting the viewer to inspect their own subjectivity as they view. This is different to the deployment of visual effects in art more generally – perspective, for example, or compositional tricks that guide the eye, in fact just about anything that identifies an artwork as art, or one art movement from another. There are edge cases. Las Meninas, for example, and Manet’s Olympia, are a direct challenge to the viewer’s viewing. Such works have a subject matter, even if it’s a bit of a decoy from the real subject matter, the viewer. The syndetic works I have made so far are almost devoid of subject matter – as is, to a large extent, pattern itself, and as are, to varying degrees, much of what was produced by P&D artists (they manage to have meaning without a normal visual subject). It’s worth noting, also, the millennia-long movement towards where “Modernist work requires autonomous spectators in self-conscious possession of their own points of view” (Benson, 2001, p. 196); you bring your own point of view, for example, to a typical (high-modern, minimalist) Agnes Martin painting.

- That essential but elusive cognitive lodestone, the self, is positioned within a body, but also within a symbolic system (language, and ‘I’ within language), an external physical and temporal location, and an interpersonal / societal-cultural landscape. Benson (2001) argues that aesthetic absorption – when looking at a painting, for example – can lead to a temporary self-quieting through a “non-deployment of I” (Benson, 2001, p. 184). He establishes the case that the self is profoundly locative. Turrell’s Ganzfeld installations disrupt location in the world and, through absorption, deployment of ‘I’ (as in ‘me’). In contrast – and although I want them to elicit temporary absorption – my planned artworks are also explicitly or implicitly interrogative. Their potential for being both pro- and anti-absorption is, given the number of possible kinds of deliberate manipulation through visual components (think pattern, metaphor, depth, rotation, rupture, text, and much more), at an almost industrial level.

- Pattern also seems to be a shortcut to both affect and identity. One major objection to P&D was that the works evoke pleasure (see Katz, 2019, and Swartz, 2007). P&D drew from applied arts, everyday design and (sometimes controversially) from non- Western traditions. Pattern also runs very strongly – and possibly increasingly – through ‘women’s art’ within Fine Art; see, e.g., Henderson (2021). It can also be a very literal form of ‘embodied cognition’, again with a strong affective component; see, e.g., Dabiri (2019). It may not be that odd that P&D is missing from the canon – P&D was strident in its multifaceted opposition to the canon.

- Damasio (2021) gives a great overview of research on brain / mind / consciousness / self. Barrett (2017) takes a compelling, emotion-first path through similar material. They and others give us sufficient scaffolding that we can think relatively coherently about how the mind works. Benson (2001) is crucial for his extended essays on the multi-layered, locative nature of self; his analyses include aesthetic experience. Hawkins (2021) makes a strong argument for how we understand the objects that make up our world.

- Barrett, L. F. (2017) How emotions are made. New York: Houghton Millin Harcourt.

More- Benson, C. (2001) The Cultural Psychology of Self. London: Routledge

- Carew, T. J. and Ramaswami, M. (2020) ‘The neurohumanities: an emerging partnership for exploring the human experience’, Neuron, 108 (November), pp. 590-593.

- Chatterjee, A. (2014) The aesthetic brain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dabiri, E. (2019) Don’t touch my hair. Allen Lane (2019), Penguin (2020).

- Damasio, A. (2021) Feeling & knowing: making minds conscious. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Danto, A. C. (2007) ‘Pattern and decoration as a late Modernist movement’, in Swartz, A. (ed., 2007), op. cit., pp. 7-11.

- Goldin, A. (1975) ‘Patterns, Grids, and Painting’, Artforum, September, pp. 50-54.

- Hartley, C. A. and Poeppel, D. (2020), ‘Beyond the stimulus: a neurohumanities approach to language, music, and emotion’, Neuron, 108 (November), pp. 597-599.

- Henderson, P.L. (2021) Unravelling women’s art: creators, rebels and innovators in textile arts. London: Supernova Books.

- Hawkins, J. (2021) A thousand brains. New York: Basic Books.

- Katz, A. (ed.) (2019) With pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972 – 1985. Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art.

- Swartz, A. (ed.) (2007) Pattern and Decoration: an ideal vison in American art, 1975 – 1985. Yonkers: Hudson River Museum.

PhD: I am honoured to be entering my second year of a part-time doctorate in Dr Brendan Rooney’s Lab in University College Dublin. Artworks in progress centre around the paraphernalia of empirical psychology. The research question itself is still under discussion (!).